Big-screen musical tells story of welder Arunachalam Muruganantham, who became a pioneer for menstrual health

Known by names like ‘Menstrual Man’ and ‘Tampon King’, Arunachalam Muruganantham is a social entrepreneur from rural Coimbatore who is changing the way rural women perceive menstrual health and has employed a million women along the way.

- He left school at the age of 14 as he lost his father and had to help his mother support the family. Not going to high school made him more curious about everything around him.

- He first thought of making a budget sanitary pad when he saw his wife using rags during menstruation. He was shocked that the sanitary pads cost Rs. 4 in 1998 when the same amount of cotton only cost 10 paise.

- When he launched his mission to produce a sanitary pad that was affordable, he was left all alone on his journey. His wife and mother left him and his village ostracized him thinking he was going mad.

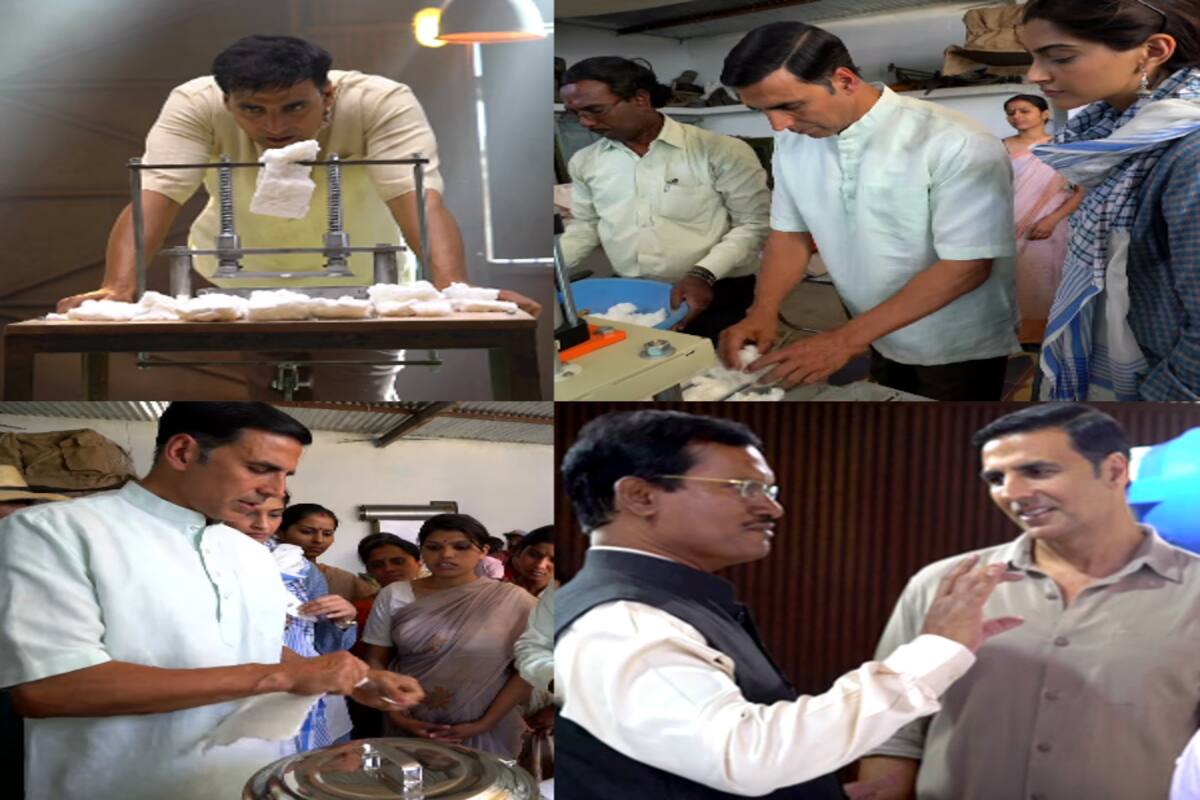

- When he discovered that multinational corporations used machines that cost millions, he resolved to make an economical machine of his own to make sanitary towels.

- In 2011, AC Nielson’s survey that was commissioned by government of India found that only 12% of Indian women used sanitary napkins. Muruganantham was taken aback to learn that these numbers were even lower for women in rural areas and these women didn’t only use rags but also other unhygienic substances such as sand, sawdust, leaves and even ash.

- His mission is not just to increase the use of sanitary pads but also to increase employment for women in rural areas. His mother suffered after his father’s death when she had to sell everything they owned and work as a labourer to support her 4 children. Muruganantham wants women to be self-dependent.

- He first launched his product in Bihar and felt if he could change mindsets there, he could succeed anywhere.

- Today he wants to spread his product’s reach to 106 countries including Kenya, Nigeria, Mauritius, Philippines and Bangladesh.

- He has installed his machines in villages and in schools so girls don’t need to drop-out from school anymore. His best moment wasn’t when he received an award from the president of India but when a woman called from a remote village of Uttarakhand where nobody had sent children to school for generations but this woman had called to say her daughter now went to school.

- Muruganantham says, “Where Nehru failed, one machine succeeded.”

Arunachalam Muruganantham, a social activist from Tamil Nadu. A welder by trade, he set about creating affordable sanitary towels after discovering that his wife, Shanthi, had been using dirty rags during her periods.

In India, only 12% of women have access to sanitary products; the rest struggle to improvise, using old newspapers, rags and sawdust. The Indian ministry of health estimates that 70% of women are at risk of severe infection because of this. One in 53 women in India will be diagnosed with cervical cancer in her lifetime, compared with one in 135 in the UK.

Nearly a quarter of Indian girls stay away from school during their period, and the difficulties they face were brought to light in August last year, when a 12-year-old in Tamil Nadu killed herself after being humiliated by a teacher in front of her class when she accidentally bled through her uniform. At the time, the only menstrual hygiene products available were expensive imports, often only sold in urban areas.

But Muruganantham’s quest to create a sanitary towel that would be cheap and easy to manufacture domestically, using locally sourced materials, was far from straightforward. For a man to drag the issue into the open was particularly controversial, especially in Muruganantham’s conservative village. In one humiliating episode, without any volunteers willing to try his prototype pad, he fashioned himself an artificial uterus made of an old ball filled with goat’s blood. When the ball split he ended up covered in blood in front of the villagers.

“I walked, cycled and ran with it under my clothes, constantly pumping blood out to test my sanitary pad’s absorption rates. Everyone thought I had gone mad. I used to wash my bloodied clothes at a public well and the village concluded I had a sexual disease.”

His quest took an emotional toll: he was ostracised by his village and his wife left him for several years, unable to cope with the humiliation. “My wife didn’t understand me. She left me. My mother left me. This topic is such a taboo, even my mother won’t discuss it with her daughter and here I was, a man, trying to do something. The community thought I was a pervert. They wanted an exorcism because they thought I was possessed by demons.”

The community thought I was a pervert. They wanted an exorcism because they thought I was possessed by demons Arunachalam Muruganantham

His breakthrough came in 2009, when he won an award from India’s National Innovation Foundation – which supports grassroots technological initiatives – to make and distribute machines for the manufacture of sanitary towels in rural communities. The machines are operated by local women in each area, which provides much-needed employment while also spreading awareness about menstrual hygiene. More than 600 machines have already been distributed in 23 states.

Way cool! Some very valid points! I appreciate you penning this write-up and also the rest of the website is really good. Laurice Shurlock Iey

For the reason that the admin of this web site is working, no uncertainty very shortly it will be well-known, due to its feature contents. Neely Jeffry Ammadis